Liberal Zionism Is Dying—It’s Time to Put It Out of Its Misery

For years, liberal Zionism let me feel principled while providing cover for injustice. It’s time to call out the illusion—and stop shielding what can’t be defended.

I have been a liberal Zionist for as long as I can remember. For much of my life, this didn’t feel like a contradiction. The idea was simple, at least on paper: combine the basic principles of liberalism—equality before the law, individual rights, a respect for minority voices—with a commitment to Jewish self-determination in the land of Israel. In a world that often demanded either unwavering loyalty to the Israeli state or outright opposition to its very existence, liberal Zionism promised a third path: a country that could be both Jewish and democratic, a place where the traumas of Jewish history might coexist with universal principles of justice.

For decades, this vision animated many in Israel and the diaspora. Liberal Zionists were not simply moderates; they were, in theory, the architects of a future in which Israelis and Palestinians alike could find dignity and security. The central tenet was always the two-state solution—an Israel and a Palestine side by side, each with sovereignty and self-determination. If enough Israelis believed in this vision, I thought, we could forge a just peace and build a nation to be proud of.

That idea, I believed, was not naïve. It was, for much of my life, the official policy not only of Israel’s left but also its political center. It was the position of the United States, of much of Europe, and of countless civil society organizations. It was also, on its face, the position of the Israeli mainstream. The belief endured that Israel’s future as a democracy and a Jewish state depended on a negotiated settlement with the Palestinians.

I clung to this faith for years, even as the ground shifted beneath my feet.

There was also, if I’m honest, a certain convenience to being a liberal Zionist.

It allowed me to hold my head high in liberal circles abroad, to see myself as moral and enlightened—a person who stood for human rights and democracy, not just for my own people, but for everyone. In the broader world, especially among progressives in the West, liberal Zionism was proof that you could support Israel and still belong to the global club of the civilized.

At the same time, it kept me anchored within the mainstream of Israeli and American Jewish life. I could participate fully in synagogues, community centers, and family gatherings without having to explain myself or risk ostracism. I could wave the flag on Yom Ha’atzmaut, feel pride at Israeli scientific achievements, and mourn national tragedies with everyone else. I could believe that my support for Israel was not an endorsement of occupation or repression, but a principled stand for coexistence and peace.

This position was, in its way, deeply comfortable. It insulated me from the sharper edges of the conflict, and from the necessity of hard moral choices. It allowed for a sense of belonging—both to the tribe, and to the world beyond it. I suspect I’m not alone in this. For many, liberal Zionism offered a way to have it all: to be both an insider and an outsider, both critical and loyal, both righteous and safe.

But convenience, I’ve learned, is not the same as integrity.

The Dream vs. Reality

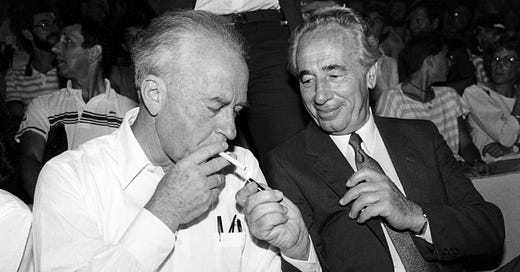

For liberal Zionists of my generation, the dream was never just a fantasy. It had a basis in history and policy, and for a time, it seemed almost within reach. The Oslo Accords, signed in the 1990s, felt like the beginning of a new era. I remember the images of Rabin and Arafat shaking hands on the White House lawn in 1993. The world seemed to exhale. The two-state solution was not just a hope; it was the official policy of Israel, the Palestinians, the United States, and the international community.

For a while, the momentum was real. The peace process brought genuine, if fragile, cooperation. There were joint economic projects, security coordination, and the gradual transfer of territory to the Palestinian Authority. Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s prime minister at the time, was no starry-eyed idealist—he was a military man who saw peace as a strategic necessity. Even some on the right, like Ariel Sharon, spoke openly of the “occupation” as a problem to be solved.

But the dream began to fracture almost as soon as it was articulated. Rabin was assassinated in 1995 by a Jewish extremist who believed that giving up land for peace was a betrayal. The Camp David summit in 2000, meant to finalize a deal, ended in failure and mutual recrimination. The Second Intifada erupted soon after: years of suicide bombings, military raids, and a deepening sense of fear on both sides. Trust evaporated.

Each round of violence and failed negotiations pushed Israeli society further to the right. The settlement enterprise, which had been steadily growing since 1967, accelerated. In 1993, there were about 110,000 Israeli settlers in the West Bank. By 2024, that number topped 500,000, not including East Jerusalem. These were not just isolated religious outposts but full-blown cities, subsidized and protected by the state.

The hope that enough Israelis would choose peace, that the arc of history bent toward coexistence, began to look less like realism and more like denial. Internationally, leaders continued to invoke the two-state solution, but on the ground, it was slipping out of reach. The gap between the rhetoric and the reality grew wider every year.

For a long time, I held on to the belief that things could be reversed—that the right leader, the right moment, the right alignment of interests could bring the dream back. But the facts were harder and harder to ignore. The reality on the ground was moving in only one direction, and it wasn’t toward peace.

The Rightward Shift in Israel

The unraveling of the liberal Zionist vision did not happen overnight. The drift to the right in Israeli society and politics has been relentless, and in hindsight, almost methodical. Each crisis—the collapse of the peace process, the violence of the Second Intifada, the frequent rounds of war with Gaza—served to harden attitudes and shrink the space for dissent.

Where the Israeli left once set the national agenda, it has become a marginal force. The Labor Party, which dominated Israeli politics for decades and signed the Oslo Accords, has nearly vanished from the Knesset. The political center, embodied by parties like Yesh Atid (Yair Lapid) and the National Unity party (Benny Gantz), has drifted rightward, embracing positions that would have been unthinkable for mainstream politicians a generation ago.

Meanwhile, the Israeli right has grown ever bolder. The settler movement, once considered a fringe, is now deeply embedded in the corridors of power. The population of West Bank settlements more than quadrupled since the early 1990s. Successive governments—left, right, and center—have poured resources into settlement expansion, legalizing outposts, and building infrastructure that cements a permanent Israeli presence in the occupied territories.

The 2018 Nation-State Law marked a watershed: it declared that only Jews have the right to self-determination in Israel, and stripped Arabic of its status as an official language. This was not an isolated move, but the legal codification of a broader shift. Policies and rhetoric that once belonged to the far right—calls for annexation, for demographic “engineering,” and for the transfer of Palestinian communities—have entered the mainstream.

October 7th, 2023, was a breaking point. The brutal Hamas attack led not only to national trauma, but also to the political ascendancy of figures from the extreme right. Ministers like Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, whose views were once considered Kahanist and beyond the pale, now hold real power. They openly advocate for policies amounting to ethnic cleansing and collective punishment. The government’s response in Gaza has been catastrophic for Palestinian civilians—tens of thousands killed, entire neighborhoods leveled—but this has only deepened the sense, among many Israelis, that compromise is impossible and that force is the only language that matters.

In the Knesset, laws have been advanced to ban Arab members for “disloyalty,” to criminalize dissent, and to strip organizations of funding for criticizing the military. In March 2024, the Knesset passed a law formally opposing the very idea of a Palestinian state. The so-called opposition, Lapid and Gantz included, have either supported these measures or declined to mount any meaningful resistance.

The Overton window has shifted so far that ideas once considered fringe—annexation, permanent occupation, and even the mass displacement of Palestinians—are now part of everyday political discourse. Liberal Zionists, who once imagined themselves as the conscience of the nation, find themselves increasingly isolated, their ideals dismissed as naïve or even dangerous.

The Israel I grew up believing in—the Israel that could be both Jewish and democratic, secure and just—is rapidly fading into myth.

October 7th and Its Aftermath

If the rightward shift in Israeli politics was already decades in the making, the aftermath of October 7th felt like an earthquake. The Hamas attack shattered not just lives but the last fragile illusions about the direction in which Israel was heading. In the space of a single day, the range of what was politically possible—and acceptable—shifted almost overnight.

The trauma and anger unleashed by the attack gave the most extreme voices unprecedented legitimacy. Calls for restraint, for distinguishing between combatants and civilians, for even the pretense of a negotiated settlement, were drowned out by a tidal wave of grief, fear, and rage. The government, already the most right-wing in Israel’s history, found itself with a mandate to act without limits. Figures like Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, who openly invoke the legacy of Meir Kahane—a man whose party was once banned for racism—now sit at the cabinet table, shaping policy.

Almost immediately, the government escalated its rhetoric and its actions. Gaza was subjected to a military campaign of historic ferocity. Entire neighborhoods were flattened, and the civilian death toll soared into the tens of thousands. The language of the state shifted as well: where previous governments might have spoken the language of “regrettable collateral damage,” this cabinet spoke of “retribution” and “erasing” the enemy. Policies that previously would have been unthinkable—cutting off food, water, and electricity to civilians, openly discussing “voluntary emigration” of Palestinians—were now debated openly in the Knesset and in mainstream media.

At the same time, the government began to take formal steps to shut down dissent. Proposals were introduced to ban Arab members of Knesset for “incitement.” Protest groups and human rights NGOs were threatened with defunding or outright criminalization. In March 2024, the Knesset passed a law making it official Israeli policy to oppose the establishment of a Palestinian state under any circumstances. The so-called centrist opposition, including Lapid and Gantz, either voted for these measures or abstained. The message was unmistakable: there is no longer any real space for dissent, for liberal values, or for even the pretense of a negotiated solution.

What was once considered the far right is now the mainstream. The energy of grief and fear has been channeled into a project of maximalism and exclusion. Any remaining hope that Israel might return to the path of liberal democracy, coexistence, and compromise now feels almost quaint.

For those of us who spent our lives believing in that hope, the events following October 7th mark a point of no return.

Liberal Zionists as Scapegoat and Cover

In this transformed landscape, the position of liberal Zionists is more precarious—and more revealing—than ever. The space once occupied by advocates for coexistence has shrunk to the margins. Those who persist in holding the flame for peace and equality, like the activists in Standing Together, do so at real personal risk. Demonstrators who mourn Palestinian lives are not just jeered; they are threatened, harassed, and branded as traitors. I know this firsthand. When I have spoken out—online or in the streets—about the suffering of Gaza’s civilians, the reaction from the mainstream has been swift and vicious. I have been called “kapo,” “traitor,” “Judenrat”; I have been told, over and over, that I am not a Jew, not a Zionist, not part of the community.

The cruelty of these attacks is not only in the language, but in what they reveal: that liberal Zionism is no longer seen as a legitimate part of the Jewish or Zionist mainstream. Its adherents are not simply mistaken or naïve; they are, in the eyes of today’s mainstream, enemies from within.

Yet, paradoxically, liberal Zionists continue to serve a purpose for the new status quo. Mainstream Zionists are quick to invoke the legacy of peace efforts—Barak at Camp David, Olmert in 2008, Rabin’s Oslo vision—as evidence that Israel “tried” every possible path to peace, only to be met with violence. The existence of a handful of Israeli peace activists is used to contrast with the supposed absence of Palestinian moderates, reinforcing the narrative that Israel seeks peace but has no partner.

Most cynically, the rhetoric of the two-state solution remains a valuable fig leaf. Even as Israeli policy moves ever closer to de facto annexation and the displacement of Palestinians, officials and their defenders continue to insist that Israel would accept a Palestinian state—if only the Palestinians were willing to make peace. This rhetorical move allows for ongoing settlement expansion and the entrenchment of occupation under the cover of “failed negotiations.” It creates the illusion of a process, even as the reality on the ground is one of permanent dispossession.

Internationally, this charade is all too effective. The United States and much of the West routinely veto efforts to recognize a Palestinian state, insisting that negotiations are the only path forward—even as those negotiations have become a hollow ritual, and Israel’s leadership shows no interest in returning to the table. The idea of liberal Zionism persists in official statements, but in practice, it serves only to shield the hard realities of permanent occupation and exclusion.

Within Israel and among its most fervent supporters abroad, liberal Zionists are tolerated only so long as they remain marginal—a convenient proof that dissent is possible, even as it is rendered powerless. Their continued presence is used to launder the image of a country that has increasingly abandoned their ideals.

To be a liberal Zionist today is to be both scapegoat and cover: reviled as a traitor when you speak out, and trotted out as evidence of pluralism when the world is watching.

The Two-State Solution as Cover for Annexation

Despite the collapse of every negotiation and the relentless expansion of settlements, the two-state solution continues to serve as a kind of diplomatic theater. Israeli leaders, when pressed by American or European officials, still invoke it—always in the abstract, always as a distant possibility. “We want peace, we want two states,” they say, “but we have no partner.” The refrain is as familiar as it is hollow.

Meanwhile, the facts on the ground tell a different story. Since the Oslo Accords, Israel has steadily expanded its control over the West Bank through a web of settlements, outposts, restricted roads, and military zones. The map of the territory today is a fractal of disconnected Palestinian enclaves, surrounded by zones of Israeli control. The possibility of a contiguous, viable Palestinian state has been all but erased—not by accident, but by design.

Government policy, especially in the last decade, has become increasingly explicit. There is no longer even the pretense of a peace process. In 2023 and 2024, the Knesset passed laws formally rejecting the very idea of a Palestinian state. Cabinet ministers openly discuss plans for annexation, and some advocate for the “voluntary emigration” of Palestinians—a euphemism for mass displacement. The government’s actions in Gaza, coupled with ongoing settlement expansion in the West Bank, signal a strategy of permanent dominance rather than negotiation.

Yet the rhetoric of the two-state solution persists, both in Israel and among its allies abroad. It serves as a shield against accountability, a way to deflect international criticism while entrenching the status quo. American administrations continue to block meaningful pressure—vetoing UN resolutions, opposing recognition of Palestinian statehood, and insisting that “negotiations” are the only legitimate path forward. In practice, Israel refuses to negotiate and works to fragment Palestinian society, making any agreement impossible.

This charade has allowed the occupation to become permanent, even as world leaders repeat the mantra of peace. Liberal Zionists, meanwhile, are left defending an ideal that no one in power intends to realize. Their continued invocation of the two-state solution, however sincere, has become a cover for policies of annexation and dispossession.

The time has come to acknowledge what is plainly visible: Israel’s leaders have no intention of allowing a Palestinian state to emerge. The two-state solution, once the rallying cry of liberal Zionists, is now a mask for the ongoing project of domination.

International Complicity and the End of the Charade

For decades, the international community—led by the United States—has played a crucial role in sustaining the illusion of a possible peace. Western leaders invoke the language of human rights, international law, and the two-state solution, but these words rarely translate into meaningful action. Instead, they function as a kind of ritual: a way to reassure themselves, and the world, that the status quo is temporary, that hope still exists, that justice may yet be achieved.

But the mechanisms of international diplomacy have become part of the machinery that preserves the occupation. The United States, in particular, has repeatedly shielded Israel from accountability—vetoing Security Council resolutions, blocking recognition of a Palestinian state, and pouring billions of dollars in military aid into the Israeli arsenal. Even as Israeli governments abandon any pretense of negotiation or compromise, American officials continue to insist that “direct talks” are the only legitimate path, effectively giving Israel a blank check to shape the facts on the ground.

Europe, too, continues to wring its hands while providing Israel with trade agreements, diplomatic cover, and tepid statements of “concern.” There are protests, there are NGOs, there are moments of outrage—but there is no sustained pressure, no willingness to risk the political cost of true accountability.

These patterns are not accidental. The international order has a deep investment in the idea of Israel as a democracy, a place that can be reconciled with the liberal values that Western nations claim to embody. The continued invocation of the two-state solution, long after its practical death, serves to protect this investment. It allows leaders to deplore the violence, mourn the tragedy, and yet do nothing to alter the underlying reality.

Meanwhile, Israel’s government works tirelessly to fragment Palestinian society—isolating Gaza from the West Bank, undermining Palestinian leadership, and encouraging emigration. The hope is not to reach a negotiated settlement, but to render the Palestinian national movement permanently weak and divided. The occupation, once described as “temporary,” has become a permanent feature, managed and normalized with international consent.

The result is a charade that benefits everyone except those living under occupation. Israel can point to international support as validation. Western leaders can maintain the fiction of a peace process. Liberal Zionists can still claim that their project is unfinished, rather than fundamentally broken.

But the truth is inescapable: the international community has enabled the death of liberal Zionism by refusing to confront the reality of Israeli policy. The pretense that the current trajectory leads anywhere but to permanent apartheid is no longer credible, if it ever was.

Liberal Zionism’s Usefulness to the Project

In this new reality, the utility of liberal Zionists to the Israeli establishment is not in their influence, but in their image. For all the fury and exclusion they face within the community, liberal Zionists remain a crucial asset for those in power. Their continued presence is deployed whenever Israel’s international reputation is on the line. “Look,” the argument goes, “we have dissent. We have internal debate. We are still a vibrant democracy. Even our fiercest critics are Jewish, Zionist, and part of our national conversation.”

This is a powerful tool in shaping perceptions abroad. When governments or organizations challenge Israeli policies, defenders can point to figures like Einat Wilf or Blake Flayton—self-described liberal Zionists who, in public forums, vigorously defend Israeli military campaigns or dismiss calls for Palestinian rights as naïve or dangerous. Their voices provide a ready-made answer to accusations of extremism: if even the “liberals” support these measures, how radical can they be?

The same phenomenon is visible in American Jewish institutions and mainstream media. Panels on Israel-Palestine almost always include a liberal Zionist, someone positioned as occupying the “moral center”—critical of some government actions, but ultimately supportive of the state and skeptical of more fundamental critique. This balancing act allows organizations to claim pluralism while excluding true dissent. The Overton window is defined so that the leftmost boundary is a liberal Zionism that has already conceded the major terms of the debate.

For liberal Zionists themselves, this role is deeply uncomfortable. Many are painfully aware of being used as a shield, a way to sanitize policies they would never have supported in theory. Some respond by doubling down—insisting that Israel’s actions, while regrettable, are always “necessary” or “forced upon them.” Others experience a growing cognitive dissonance, torn between their ideals and the realities they are called upon to justify.

But the cold truth is that liberal Zionism’s primary function today is to provide cover. Its continued existence—highly visible, but politically powerless—serves to legitimate a system that has moved far beyond its founding ideals. Inside Israel, liberal Zionists are tolerated only as long as they do not meaningfully threaten the status quo. Abroad, they are a talking point, a fig leaf, a mask for the project of permanent domination.

To be a liberal Zionist now is to be both a symbol of conscience and an unwitting accomplice. The movement’s ideals are invoked to justify the very actions that betray them.

Conclusion: The End of the Illusion

For years, I tried to hold on—to the ideals, to the hope, to the identity of a liberal Zionist. I wanted to believe that it was still possible to reconcile my commitment to Jewish self-determination with my belief in equality and justice for all, including Palestinians. I argued, marched, and wrote, insisting that the better Israel I loved was still within reach if only enough of us held the line.

But experience has a way of stripping away illusions. The shift in Israeli politics, the relentless expansion of settlements, the normalization of ideas that once belonged to the far right, and the brutality of recent wars—all have forced me to confront a painful reality. Liberal Zionism, as a living political project, is dead. Its language still circulates, but only as a mask—shielding a status quo of occupation, dispossession, and exclusion that it cannot meaningfully challenge.

My own journey has been marked by loss. I’ve lost my place in communities I once called home. I’ve lost the comfort of thinking I could be both an insider and a critic, both participant and conscience. And I’ve lost the ability to believe that Israel’s trajectory is an aberration, rather than a logical endpoint of a project that was always more exclusionary than I allowed myself to see.

When I speak out now—whether about the suffering in Gaza, the erosion of democracy within Israel, or the complicity of American Jewish institutions—I am told I am no longer a Jew, no longer a Zionist, no longer one of us. The sting of these words is real, but what hurts more is the realization that, in some sense, they are right. Zionism as it is practiced today has no room for my values or my voice. Liberal Zionism is kept alive only as a convenient fiction, a fig leaf over a reality that demands our silence or our complicity.

To persist in calling myself a liberal Zionist would be to participate in that fiction. If I care about integrity—about justice, about honesty, about the future—I have to let it go. The project I believed in is gone. What remains is the work of mourning, of solidarity, and of imagining something new. For now, I am left with grief, with anger, and with a stubborn refusal to be silent. If there is a future for justice between the river and the sea, it will not come from the illusions of the past, but from the courage to face what is, and to fight for what ought to be

.